Articles

The third meeting of What’s Next was another lively and informative discussion of what people are experiencing related to the Covid-19 pandemic and what we are likely to see moving forward. The participants were from a diverse cross section of society including nurses, physicians, social worker, and several folks from outside of healthcare including an academic administrator, and human rights lobbyist. This week’s session focused on Augmented Intelligence (AI) the use of technology to enhance existing ways of doing work. Some of the key themes related to AI advantages, barriers/obstacles, and potential solutions were presented:

EVOLUTION OF AUGMENTED INTELLIGENCE

The history of how Artificial Intelligence stretches back to the 1950’s, when generation of scientists, mathematicians, and philosophers like Alan Turing, Marvin Minsky and John McCarthy explored the possibility of computers augmenting human intelligence. AI has been defined as an area of study in computer science concerned with “the development of computers to engage in human-like thought processes such as learning, reasoning and self correction” (Dilsizian & Siegel, 2014). The term Augmented and Artificial Intelligence are often used interchangeably. The main difference is, augmented means to make something greater, and indeed that is ideally the role of AI, which encompasses various technologies to enhance healthcare.

Around the world, every health care systems struggle with rising costs and uneven quality of care despite the hard work of well-intentioned, well-trained clinicians. The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) in the era of big data could assist clinicians in shortening processing times and improving the quality of patient care in clinical practice. Clinicians diagnose diseases based on personal medical histories, individual biomarkers, and their physical examinations of individual patients. In contrast, AI can diagnose diseases based on complex algorithms using hundreds of biomarkers, imaging results from millions of patients, aggregated published clinical research from PubMed, and thousands of physician’s notes from electronic health records (EHRs) (Krittanawong, 2018).

AI KEY IMPACT AREAS IN HEALTHCARE

According to our research, AI has the potential to impact healthcare in four key areas:

1) Diagnostics and Interpretation: AI is already being used to enhance the reading and interpretation of diagnostic images in radiology and data collected in Genomics.

2) Task Automation: AI is being used to collect data for triaging patients in ER’s and clinical practices. AI is also being used to automate appointments and scheduling.

3) Education/Research: Here AI is being used in education, research, and development. One example is Adaptive Learning where on-line modules give quizzes during the module, interpret the learners knowledge, and then adapt the next steps of the workshop to focus on the participants learning needs.

4) Clinical Decision Making: This area is perhaps the most exciting application of A.I for medical knowledge has moved beyond the capacity of effective human interpretation of data points. One example is allergies and medication incompatibilities. While it is the responsibility of nurses and physicians to review a patient’s at-risk comorbidities, allergies, and medications, it has become so complicated it is virtually impossible to do that given the busy nature of healthcare. Thus, AI applications can do this, much like the computer on an airplane does for pilots.

AI BARRIERS/OBSTACLES/POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS

TECHNICAL PLATFORMS

The technology to create AI has been going on for over 20 years, however its use has been sporadic mainly due to lack of a standard platform, resistance to change, and business concerns. The reaction of the participants was pretty typical:

a) I prefer a live person

b) How can a computer replace a human

c) It seems to impersonal

d) What about the people who will lose jobs?

e) What about underserved populations who don’t have access to technology?

While all these reactions reflect the reality of people’s concerns, AI is already part of our daily life including:

a) Robot enhanced surgery

b) Virtual nursing assistants that monitor at risk patients

c) Administrative workflow assistance

d) Fraud detection

e) Dosage error reduction applications

f) Connected machines

g) Clinical Trial Participant Identifiers

h) Automatic Image Diagnosis in Radiology

i) Cybersecurity

The cost savings of these AI technologies is estimated to be $150 billion in the U.S. alone (Accenture report). These enhanced platforms can integrate with the hospital/practice EMR, leverage the established workflows, and ensure that the patients’ receive state-of-the-art care.

FINANCES

Finances impact AI in two ways; how will we pay for it and how will reimbursement be handled. Reimbursement has been shifting toward a value-based payment model that provides incentives for care delivery in the lowest-cost care settings, the identification of and interaction with high-risk persons before disease onset, the efficient use of integrated care teams, and outcomes. AI promises to improve outcomes. If that proves to be true, it will be reimburse by insurance companies and the government.

Many of the AI applications suggest improved outcomes when compared to human face-to-face care. As was suggested around Telehealth, the issue is Who gets to realize those savings: the hospital, the insurance company, or the consumer? As was discussed in the previous sessions of What’s Next, the various stakeholders may shift their argument about AI once the see positive results. Ultimately, the decision is likely to be determined by consumers including the patients and businesses that purchase insurance policies based on their employee’s desires.

However, depending on the decision insurance companies and policy makers make regarding reimbursement for AI, hospitals may move slowly in introducing AI applications in the workplace.

PROVIDER/CONSUMER ADOPTION

People are growing fatigued with the pandemic situation and are becoming increasingly concerned about their personal safety. People who frequently access the healthcare system may manifest the most grieving reaction (Kubler-Ross & Byock, 2014) going through denial, anger, bargaining, until they finally reach acceptance. Vulnerable groups (the poor, Native Americans, Nursing Home residents, people with behavioral health issues, and underrepresented minorities) have an increasing risk of not being treated because of lack of access to technology. There is a need for more economical care with improved outcomes and AI can assist in achieving those goals.

One of the analogies that is often used to describe change theory is, the horse is out of the barn. The pandemic has forced us to use different forms of AI and providers and patients may not want to go back to the way things were. Senge (2006) suggested there is a dynamic tension between the current reality and vision for the future. The ending of the current reality is a bigger step in terms of change than the allure of the new product or system (Bridges, 2004).

Front-line workers are consumed with tasks at hand and day-to-day challenges, which often translates to keeping systems status quo. AI may be a higher order approach (Carpenito-Moyet, 2003) requiring discussions and planning for the changing future. (Kuhn, 2014) suggested people will resist change the closer they are tied to the history, or current reality. Thus, the younger generation who are more technically savvy and have less history of accessing healthcare are likely to embrace AI applications.

REGULATORY/LEGAL

One of the interesting unintended consequences of the federal government’s resistance to address the pandemic as a nation is that it has forced states and local governments to address the problems, resulting in the emergence of innovative solutions including emerging AI technology. Bridges (2004) suggested the turmoil of massive changes, creates a ripe environment for innovation as bureaucratic rules are not in place yet to oppose innovation.

Clinician’s license portability and interstate licensure a key building block to the scalability of AI applications. To tackle Covid-19 situation, state officials may have to take emergency actions to ease the rules on AI But, we need standardized rules and regulations across the nation on a permanent basis to avoid malpractice concerns for clinicians regarding different liability laws, statutes of limitations, standards of care or damage caps, and medication prescription across state lines.

One important goal for the early adopters of AI must be to educate legislators to the importance of creating laws that are user friendly. For instance, most metrics today are based on hands-on encounters. How do we get legislators and insurance companies to alter the metrics to view AI as a legitimate medical intervention?

FUTURE OF AI

AI has probably reached the tipping point (Gladwell, 2014) and is here to stay. There probably is no going back to the way things were. There are certain situations where AI is now the state-of-the-art. While there may be some pushback around AI it is slowly being incorporated. Work will need to be done around the logistics, finances, and existing rules for the use of some AI Higher education must look at orienting future clinicians to the use of AI as it becomes more of a standard practice. The goal is to provide the best clinical outcomes and if AI can enhance that it will be used more and more.

As we witness technology becomes more intertwined with medicine, the symbiosis of precision medicine and AI cognitive systems capabilities will help clinicians to speed up the diagnoses and treatment decisions so that they can spend more time taking care of the patients, which every physician love to do. The key to adoption is that ” AI needs to be embraced, not feared “.

REFERENCES

Accenture Report. https://www.accenture.com/us-en/insight-artificial-intelligence-healthcare%C2%A0

Bridges, W. (2004). Transitions: Making Sense of Life’s Changes, Revised 25th Anniversary Edition. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press.

Carpenito-Moyet, L. J. (2003). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs-revisited. Nursing Forum, 38(2), 3-4.

Dilsizian, S. E., & Siegel, E. L. (2014). Artificial Intelligence in Medicine and Cardiac Imaging:

Harnessing Big Data and Advanced Computing to Provide Personalized Medical Diagnosis

and Treatment. Current Cardiology Reports, 16(1), 441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-013-0441-8

Gladwell, M. (2014). The Tipping Point. New York, NY: Time Warner.

Krittanawong, C. (2017). Healthcare in the 21st century. European Journal of Internal

Medicine, 38, e17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2016.11.002

Kubler-Ross, E., & Byock, I. (2014). On Death and Dying: What the Dying Have to Teach Doctors, Nurses, Clergy and

Their Own Families. New York: Scribner Publishing.

Kuhn, T. S. (2012). The Structure of Scientific Revolution: 50th Anniversary Edition (4 ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Senge, P. M. (2006). The fifth discipline the art & practice of the learning organization revised

edition. New York: Random House.

ABOUT THE HOSTS

| Saravana “Samy” Govindasamy is a success-driven, entrepreneurial leader with 20+ years of progressive experience in management, strategy, innovation, and technology consulting Samy has held executive leadership positions and spearheaded innovative enterprise-wide transformation programs/projects in excess of across the full continuum of care for medium and big health systems by establishing PMO/innovation centers using design thinking and agile methodologies.

Samy also possesses Big 4 consulting experience. Throughout his consulting career, Samy has built a reputation for achieving bottom line results, effectively aligning business and technology needs, and leading and developing high-performance teams for Fortune 50 global organizations. Samy’s educational background includes a Doctorate in Business Administration, Fox School of Business, Temple University, Philadelphia, USA, Master of Business Administration, and a Bachelor of Engineering. Samy holds Project Management Professional (PMP) and Lean Six Sigma in Healthcare certifications. Samy has published papers in refereed journals and has delivered professional speaking engagements in the areas of healthcare innovations, strategy, operations management, project/program management and process improvement. |

| Michael Grossman has been a nursing leader for over 40 years in a variety of clinical settings. Grossman is certified as a Nurse Executive Advance-Board Certified (NEA-BC) and Nurse Manager Leader (CNML). He has worked in a variety of roles including staff nurse, clinical nurse specialist, manager, director, coordinator of leadership development, and nurse entrepreneur.

Grossman is a frequent national speaker on a variety of topics including leadership, change, quality improvement, teamwork, and working with emotionally difficult patients and families. Grossman earned his doctoral degree in management of organizational leadership from the University of Phoenix. He is a graduate of Widener University where he received his BSN and MSN in Emergency and Critical Care nursing. He also has a BA from Temple University in Psychology. |

There was a battle between science, business, and politics which affected the narrative of what was going on and lead to an emergence of conspiracy theories. People are growing fatigued with the situation and become increasingly concerned about their personal plight depending on how secure their income and job situation is. There is a need for addressing the psychological needs of people.

Emerging technologies (Artificial Intelligence/Telehealth) has probably reached the tipping point in healthcare industry and is here to stay. There probably is no going back to the way things were.

When it comes to survival, living in a group offers many perks, the most important one is the feeling of sense of safety and security that allows us to concentrate on making progress by not facing the threats alone. Organization leaders are reframing the dialogue using different approaches.

TAKING A PROJECT MANAGEMENT APPROACH

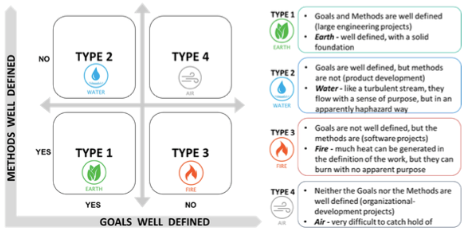

Projects should be judged against two parameters:

- How well defined are the goals

- How well defined are the methods

(Turner & Cochrane, 1993) created a goals-and-methods 2 x 2 matrix that defines four types of project. Organizations should use different techniques to handle the different types of projects. These different types of projects require different techniques and execution methods to be adopted. Organizations should negotiate agreement of the goals and brainstorm methods of achieving them where they are ill defined with key stakeholders, as shown in Figure 1 below.

Countries handled the pandemic situation in different ways: Some countries (South Korea) handled it as a Type 1 project with greater chance of success in controlling the transmission by clearly defining the methods (social distancing, using masks, tracking the incidence, etc.) and taking a bottom-up approach. Other countries handled it as a Type 4 project and struggled to define the methods and in establishing clear goals using more of a top-down approach (U.S.). And some countries started as a Type 4 and quickly took corrective measures and moved to a Type 1 approach.

Figure 1: Goals vs Methods (Turner & Cochrane, 1993)

IMPLICATIONS

The point of this discussion is not to evaluate the effectiveness of the various approaches from a clinical perspective, but to highlight the virtues of Project Management. Of particular concern should have been the safety and morale of front-line essential workers in hospitals, food preparation, distribution, law enforcement, and the military. Project Management clearly improves employee engagement which is related to being:

- Clear about expectations

- Having the right equipment

- Getting feedback

- Feeling their opinion counts

- Having a mission/purpose they agree with

- Feeling that their role is meaningful

Essential workers clearly did not feel safe, properly equipped, or adequate compensated for the risk they were taking to themselves, and their families who they might infect.

Sweden and South Korea had clear, well defined approaches, whereas the U.S. approach was an air approach, difficult to catch a hold of in terms of goals and methods (Turner & Cochrane, 1993). The plan was constantly shifting, expectations were not clear, equipment was lacking, and the majority of people disagreed with the approach, especially around sharing information with other countries and working together. This approach also left stakeholders confused including manufacturers of supplies, testing centers, health care providers, and other nations we previously were aligned with.

If a project management approach was applied in the US there would have been a clearly defined Executive Sponsor Team, well defined goals, and methods used that were monitored through testing and data analysis and led to a greater probability of success. Without those things in place the U.S. population was susceptible to debates around science vs business, which ultimately led to conflict, mental fatigue, frustration, and an inability to objectively evaluate the outcomes.

What does this say about your own organization? How can innovative project management approach guide the mission, vision, values, and goals of your organization, given the various challenges you face?

CHALLENGES

There were various challenges raised by the participants in today’s session:

- Everyone is looking to someone else to step up and provide leadership during these chaotic times

- The corporatization of healthcare has gotten in the way of some human needs

- How do we get health care providers to see things from the patient perspective

- Who are the other stakeholders in healthcare (Insurers, pharmaceutical companies, equipment manufacturers, stockholders) and how do we address their needs

- Politics obstructs action, but how can politics be harnessed to accomplish positive things?

- How do we recognize and address racial inequality?

- What are the specific needs of the aged population who are being affected by Covid-19 at an alarming rate?

- What can we as individuals do to make a difference?

- How do we close the knowledge gap? What sources can be trusted to provide accurate information?

- How can we put a face to the impact of Covid-19; 100,000 deaths is just too large a number to grasp. These were human beings with lives that matter to their loved ones.

- We need a business case to get something meaningful done. Unless you have buy in from politicians, organization leadership, and funding sources nothing will get done

- When there is a void in leadership, it provides an opportunity to try different things

- Corporations need ways to monetize any suggested solutions

REFERENCES

Turner, J. R., & Cochrane, R. A. (1993). Goals-and-methods matrix: coping with projects

with ill-defined goals and/or methods of achieving them. International Journal of project management, 11(2), 93-102.

ABOUT THE HOSTS

| Saravana “Samy” Govindasamy is a success-driven, entrepreneurial leader with 20+ years of progressive experience in management, strategy, innovation, and technology consulting Samy has held executive leadership positions and spearheaded innovative enterprise-wide transformation programs/projects in excess of across the full continuum of care for medium and big health systems by establishing PMO/innovation centers using design thinking and agile methodologies.

Samy also possesses Big 4 consulting experience. Throughout his consulting career, Samy has built a reputation for achieving bottom line results, effectively aligning business and technology needs, and leading and developing high-performance teams for Fortune 50 global organizations. Samy’s educational background includes a Doctorate in Business Administration, Fox School of Business, Temple University, Philadelphia, USA, Master of Business Administration, and a Bachelor of Engineering. Samy holds Project Management Professional (PMP) and Lean Six Sigma in Healthcare certifications. Samy has published papers in refereed journals and has delivered professional speaking engagements in the areas of healthcare innovations, strategy, operations management, project/program management and process improvement. |

| Michael Grossman has been a nursing leader for over 40 years in a variety of clinical settings. Grossman is certified as a Nurse Executive Advance-Board Certified (NEA-BC) and Nurse Manager Leader (CNML). He has worked in a variety of roles including staff nurse, clinical nurse specialist, manager, director, coordinator of leadership development, and nurse entrepreneur.

Grossman is a frequent national speaker on a variety of topics including leadership, change, quality improvement, teamwork, and working with emotionally difficult patients and families. Grossman earned his doctoral degree in management of organizational leadership from the University of Phoenix. He is a graduate of Widener University where he received his BSN and MSN in Emergency and Critical Care nursing. He also has a BA from Temple University in Psychology. |